- 6 mins read time

- Published: 29th July 2020

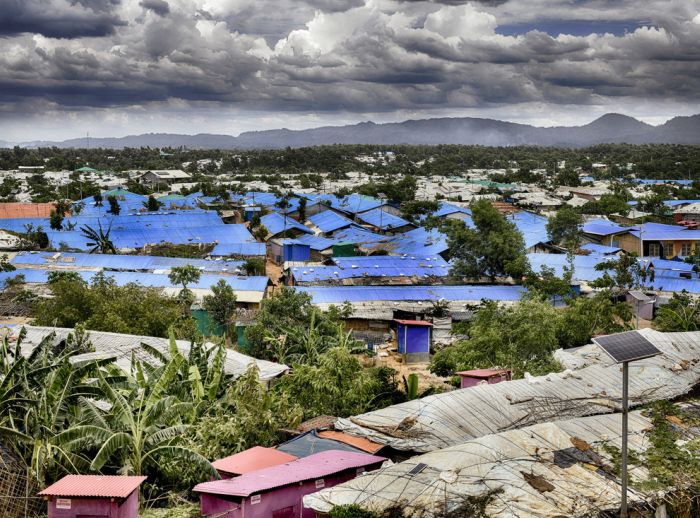

Photographing the pandemic – Fabeha Monir in Bangladesh

Fabeha Monir is a Dhaka-based visual journalist and member of Women Photograph. Her work explores themes of social development, migration, gender-based violence and forced exile in marginalised communities. Fabeha told us about her experience documenting the impact of COVID-19 on Rohingya people living in Cox’s Bazar – home to the world’s largest refugee camp.

“When I was working with Oxfam to report on the impact of COVID-19, Cyclone Amphan hit. It created fear. In most of the Rohingya refugee camps, there are no cyclone shelters.

“I have covered major disasters, but nothing like this before. The fear and grief people hold is contagious. COVID-19 is everyone’s fight.

“Upwards of 60,000 to 90,000 people are crammed into each square kilometre of the camp, with families of 12 sharing small, flimsy shelters. Everyone is breathing the same air inside that shelter, coughing and sneezing. The 34 camps have a population density more than 40 times above the average in Bangladesh.

When I interviewed and photographed Nur, it was just as the cyclone was starting to hit.

“She walked with her baby in her arms on a narrow path between the temporary homes and went to wash her hands with the contactless handwashing device that Oxfam had installed. Hunger, a lack of water and COVID-19 has made people’s lives miserable, but Nur still has strength. Nur and her daughter left an ever-lasting impression on me.

“Super-cyclone Amphan left a trail of devastation throughout north-east India and the Bangladesh coast, with over 80 deaths reported. Thousands of homes and crops were destroyed, compounding the suffering for many communities already hit by COVID-19 and the impact of lockdown.

“In the camps, Oxfam, partner staff and Rohingya volunteers were on the ground making preparations before the cyclone hit, which was encouraging to see and document. I met 24-year-old Abul Alam, who was spraying disinfectant in the drains and alleys, and Md. Yusuf and Abu Nayeem, who were securing the water tanks with ropes. Their commitment to serve the community impressed me a lot.

Water is essential, especially during the pandemic.

“Shortages of water can cause disputes. Under these circumstances, it’s incredible to see how Oxfam is supporting the Rohingya community with their contactless handwashing devices and providing drinking water for the majority of the camp.

“I am working hard to tell stories that matter. But this fight is no more a lonely battle. We are all in this together.

“I am not on the ground to just report on the deaths. We need to highlight the struggles of people who have no access to isolation or safety. In any system of oppression, the most vulnerable will always suffer the most and be heard the least. Violence against women has increased. Homeless women and children, transgender people, sex workers and the refugee community are all suffering from this crisis.

Every time I take a photograph of someone, I become responsible for their history.

“The photographer provides the first line of ‘ethical defence’. They must follow the ethical code of practice and take responsibility for the images they capture. Photography can show the horror of war, the tragedy of an incident and the hardship of poverty, providing information that can be critical for decision-makers.

“I often ask myself how my stories can drive change. Visual journalists play an important role, providing vital information to communities affected by crisis. We have to continue to question how we tell these stories, make an impact, and minimise risks, both for our subjects and ourselves.

As a journalist and photographer, I work very closely with people.

“While this is an important story, it must not come at the expense of our health. I have to remind myself to maintain physical distance while I work. Wearing protective gear and breathing in it is hard. It can also be unnerving disinfecting myself every other minute. I must stay calm, not rush, and focus on what’s important.

“When I return from work and edit my images, I feel strange. I do not know when this pandemic will end, how people who live at the edge of society will survive. The family who have a little rice left in their kitchen; how will they continue living and dreaming for tomorrow?

There is no separation between my life and work.

“We can’t unplug from the suffering we are also experiencing while covering the pandemic. I look to the courage and strength of the people I photograph – this gives me the ability to wake up each day and continue reporting.

“Without any warning, our lives have now shifted from order to chaos. We cannot make plans. We are restless, not knowing what will happen next. But the astonishing part of covering this historic time is the acts of solidarity.

“We are more united mentally and spiritually than we have ever been before, though we have to distance ourselves physically.

“We are unique. We haven’t given up hope. While working closely with health professionals, humanitarian workers and security personnel, I have learned we must continue our work.

“When I document the lives of refugees, or the struggle of a single mother working to feed her children, it reminds me how we have to hold on to hope. If we let the pandemic take that away, there will be no way we can come out of it alive.”

*Name changed to protect identity.