Malawi’s 2025 elections marked a turning point for women’s political leadership in the country. Few stories capture that shift better than that of 34-year-old Hon Khadija Leah Chunga, the newly elected member of parliament (MP) for Lilongwe Kamphuno Constituency.

When Malawians went to the polls to vote in the General election on 16 September 2025, the country renewed its democratic mandate, but it also inched forward on women’s political representation. A historically high number of women were elected to the National Assembly (the country’s supreme legislative body). This included younger women and women from districts where female leadership has traditionally been rare. Long-term investment in gender-transformative democracy is starting to show results.

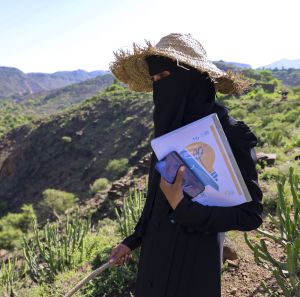

One of the new faces in Parliament is Hon Khadija Leah Chunga, who is MP for Lilongwe Kamphuno. Khadija is a young mother, whose election journey was not easy, as she was entered a male-dominated political space without the full backing of a party machine. However, her close community ties led to her being elected. She took part in Oxfam’s Reducing Poverty and Inequality in Malawi project implemented in partnership with CYO, CAVWOC and CEWAG. The project works with women to build leadership skills, promote peaceful and inclusive elections, and expand space for women and young people in Malawi’s democracy. Women transformative leadership initiatives are implemented by Oxfam in Malawi and partner organisations with support from Irish Aid and the European Union.

A political dream that started in her mother’s salon

Khadija didn’t just wake up one day and decide to be an MP. As a girl she spent time in her mother’s beauty salon, where women politicians used to come to “do their nails” and talk politics. That space became her quiet classroom.

She listened to them discuss development, hospitals, schools, how to support women in their constituencies.

“I was impressed. I never heard women speaking badly about their constituencies. They always wished the best. That’s when I said, I can also do this.”

That early exposure matters. It shows why informal, women-led spaces, salons, savings groups, church groups are powerful entry points for political leadership.

Breaking family expectations and fears

Like many Malawian women who stand for office, Khadija had to start by persuading those closest to her.

“My family was scared. They said, ‘Politics is dangerous, they will kill you.’ I am the last born, and no one in my family is a politician. But my husband supported me. And now that I have won, there is celebration in my family.”

Her story reflects what women candidates across Malawi shared in the run-up to the elections, getting onto the ballot is not only about public acceptance, it may also involve overcoming private resistance and fear inside families. That is why Oxfam and WOLREC paired leadership training with confidence-building, mentoring and peer spaces for women aspirants.

When the primaries close the door

Khadija first sought nomination through a mainstream political party. Like many women, she found that internal party processes did not always reward merit. Party primaries in February 2025 were painful. She was popular on the ground, but the party preferred another candidate.

“It was a torture for me. I cried. But I had already seen myself in Parliament, so I did not stop.”

Rather than stepping back, she ran as an independent candidate without the support that party-backed candidates have.

This is her key lesson from 2025, women are increasingly confident to contest outside party structures, but they still need resources to compete fairly.

The power of mentorship and women’s platforms

Khadija repeatedly credited the trainings delivered by WOLREC, with support from Oxfam and the EU, for sharpening her political skills.

“When you go to that training, you don’t come back the same. We learnt how to speak to churches, to schools, to villages, to different people in different ways.”

She wants that support to continue now that she is in Parliament.

“You taught us how to campaign, now teach us how to work as Members of Parliament.”

Winning without large funding

Campaign financing remains one of the biggest barriers for women candidates in Malawi.

“I did not even have one million kwacha in my account (about €540). I was using money from my family’s car-hire business.”

While some contenders could afford big rallies, transport and constant visibility, Khadija chose proximity over spectacle. She walked to meet people, visited households, and invested in small but tangible development starters to demonstrate her commitment. This included a few iron sheets for a clinic roof, some cement to repair a building, paint for a classroom with a promise to secure funding for the rest after election, to show people what she would prioritise once elected.

“Money you get today cannot feed you for five years. What you want is development.”

Smart, underdog campaigning: “I campaigned with the children”

One of the most creative parts of her campaign was how she planned her rallies around her opponent’s rallies. She didn’t have party transport or endless fuel, so she and her team often waited for the better-resourced candidate to finish in one area and then moved in just after, with her own sound system, music and a very clear message.

“When they finished, I came with my music. Children knew my car because of the sweets. They ran to me. When the children are happy, the mothers listen.”

“In my constituency, even a five-year-old can tell you who Khadija is.”

Why inclusive leadership matters in Lilongwe Kamphuno

Khadija is very clear about what her constituency needs, starting with roads and connectivity to reduce isolation, especially for rural parts of the constituency. Equally important are health and education.

“We only have private hospitals. People walk 25–30 km to reach a government hospital. Pregnant women are delivering at home because private clinics charge about MWK 120,000 (about €65).”

“We can build classrooms, but if we don’t have teachers, we are just building walls.”

This is where her promise to pay the MWK 1,500 (about €0.80) school development fee for children in her area is so politically smart, it links her campaign to a concrete household burden.

“I told the children: go and tell your mothers, ‘If you vote for Khadija, you will not pay the MWK 1,500.’ So, I have started paying it from my own money.”

From representation to transformation

“I will be there to speak on their behalf. I will be there to encourage the young girls. We can do it, and we will make Malawi proud.”

“Our voice to be heard there, it will not be easy. There are many men. But I have the courage.”— Hon Khadija Leah Chunga, MP for Lilongwe Kamphuno

This is the heart of Oxfam’s Transformative Women’s Leadership approach in Malawi:

- get women in,

- support them to influence,

- shift social norms so that women’s leadership is expected, not exceptional.

The project was Co-Founded by the European Union.