- 7 min read

- Published: 25th July 2022

Not all refugees in the EU are being welcomed with open arms

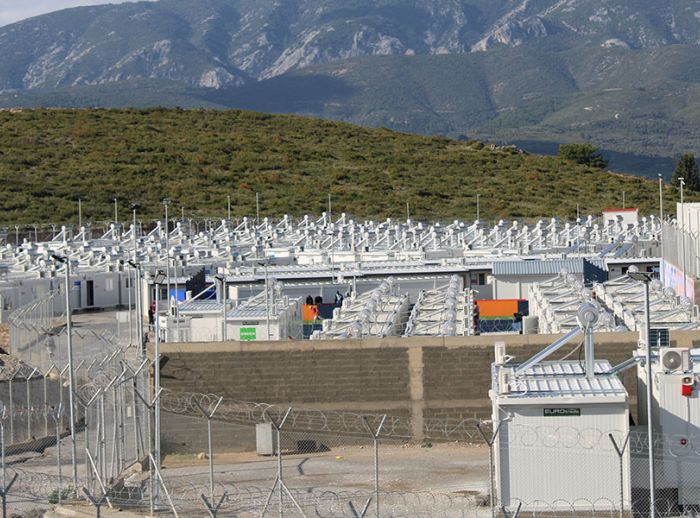

We arrived at the ‘closed controlled access centre’ or closed refugee camp on Samos island after a scenic but zigzagging drive from the closest town of Vathi, 9km of mountainous, twisting road away. In the company of two Greek lawyers from Oxfam’s local partner organisation, the Greek Council for Refugees, I stood outside the gates of the camp for half an hour while the private security guard checked our documents and called the Ministry to verify the permission to enter that we had shown them.

I felt like I was at a prison camp when I saw the elevated watch towers, the double layer of barbed wire surrounding the camp, the high metal wire gates that people enter and leave through and the CCTV tracking every move and streaming it directly back to the Ministry in Athens. When the speakers crackled to life and boomed out in different languages that there would be a census head count of residents that day it only added to that impression. There was a heavy security presence with several police and private security company cars and jeeps parked around the entrance and a few large clusters of security guards standing around.

Resident asylum-seekers are only allowed to leave and enter the camp at certain hours (there is an 8pm curfew) and to enter the camp you pass through turnstiles, magnetic gates and x-rays and scan one’s fingerprints and asylum card. Security guards also do body and bag searches of residents. I was visiting the camp with Greek Council for Refugees (GCR) as part of a research project that was collecting information and resident testimonies for Oxfam and GCR’s bulletin on closed camps (that you can read here).

During our time on Samos, residents and service providers told us about the closed camp’s devastating impact on the mental health of residents, how it has made it more difficult for them to access lawyers (essential for having fair access to applying for asylum), made it virtually impossible to access health care and isolated residents from the community on Samos.

Although Samos Island might seem far away from Ireland, Ireland is strongly linked to this camp and the other four being built on Greek islands because these closed camps are 100% EU funded, so Irish money has contributed to buying the barbed wire and the metal fences that close asylum seekers off from the local community.

It is also important to remember that the policies that keep asylum seekers contained to Greek islands are EU policies and so the Irish government is part of making these policy decisions through the EU Councils of Ministers.

Detained without notice or legal basis

On 17 November, a few weeks before our visit, camp management introduced a new rule that anyone who didn’t have a ‘valid asylum card’ could no longer leave the camp. This meant that around 100 of the 450 residents were given no notice that suddenly they were indefinitely detained in this camp[1].

Οn 17 December 2021, the Administrative Court of Syros[2] confirmed that the prohibition of exit from the Samos CCAC imposed by the Greek state was unlawful. However, residents in the camp reported to the Greek Council for Refugees that the ban was still in place even after the court decision.

“I have suffered mentally a lot.</strong> I suffer from traumatic experiences in my country and unbearable living conditions here. My mental health has been destroyed. It’s been three years now since 2019. I cannot understand why I haven’t succeeded in committing suicide. And now I am being held prisoner here….. I just want to go outside. They don’t let me. They are keeping me here as a prisoner."— Testimony (received 12/2021) of an Afghan young man trapped in Samos since 2019, pending the examination of his subsequent asylum application.

Mental Health Impact

All of the residents I met spoke about the stress and trauma they suffer that stops them from being able to sleep at night. Residents said that being able to leave the camp and go to language classes or to a community centre helped to take their minds off their stress. The fact that the camp is so isolated and remote and the process of passing through security to leave and enter has meant that many people no longer leave the camp and this has a very negative impact on their mental health. Médecins Sans Frontières/ Doctors Without Border (MSF) reported that the majority of their mental health patients on Samos present symptoms of depression and PTSD (Post-traumatic stress disorder) and linked the deterioration of these people’s mental and physical well-being to living in the new closed camp.

Access to lawyers and health care

Those providing legal support to asylum seekers in the camp said that they faced delays and challenges trying to meet their clients in the camp. They have to email for permission in advance of their visit and reported waiting for an unreasonably long time at the gate for their entrance to be approved and being followed by security guards inside the camp while visiting their clients.

Residents in Samos CCAC have limited access to healthcare. There is no doctor or medical staff based inside the camp, and residents must rely on the sporadic visits of a military doctor.

“A new chapter in migration management” for the EU?

Refugees and asylum-seekers have for many years been housed in inhumane and undignified conditions in a number of EU countries, including Greece where they sleep in tents in extreme heat of summer and the snow and rain of winter in overcrowded camps without adequate hygiene and toilet facilities. The EU and the Greek government have praised the new ‘closed controlled access centres’ as the solution to these inhumane conditions because these closed camps have more sanitation facilities and containers instead of tents. The EU and Greece plan to open closed centres on five islands: Leros, Kos, Lesbos, Chios and Samos. The camp on Samos that we visited was the first to open and the ‘blueprint’ for future camps.

EU officials have called these closed camps “a new chapter in migration management” but there is cause for concern about what that this “new chapter” looks like when the camps are like prisons and the Greek Minister for Migration has explicitly said that “the new closed controlled structures act as a deterrent[3]” to people fleeing to come to the EU to look for protection.

Everyone fleeing persecution or serious harm in their own country has the right to ask for international protection. Seeking asylum is a fundamental right and enshrined in both the 1951 Refugee and in Article 18 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Making conditions bad in camps as way of deterring people fleeing from seeking protection in Europe is not in line with our responsibilities. This is especially so in a context where 83% of the refugees in the world are hosted in low and middle income countries[4].

Ireland has a responsibility to advocate for change

The EU is negotiating a New Pact on Migration and Asylum at the moment that is supposed to recognise these past failings. However, the policies on the table fail to address the flaws that have led to the overcrowded and inhospitable conditions in Greece. As an EU member state, Ireland is involved in negotiating the New Pact on Migration and Asylum. The Irish Government should push for real responsibility sharing by relocating asylum seekers from border states to other EU member states, including Ireland.

In the short term, Irish Ministers urgently need to highlight the need to improve conditions in camps with their Greek counterparts and call for the establishments of a human rights monitoring system for these EU funded camps. In the longer-term, Ireland needs to encourage the Greek government and the European Commission to abandon the policy of closed camps and instead allow people to move freely while having their asylum-applications assessed, as they have committed to do in Ireland, by agreeing to close the direct provision system.

- People without asylum applicant cards are newly arrived persons waiting for a card to be issued, persons with second-instance negative decisions that have not registered or cannot register a subsequent asylum application, persons who have registered a subsequent application, and those with a first-instance negative decision waiting for an appeal.

- ruling in the case of an Afghan resident of the facility and represented by GCR

- Ν. Μηταράκης: ”Προχωρήσαμε σε αποσυμφόρηση και των νησιών, και της ενδοχώρας και της Αθήνας – Οι νέες κλειστές ελεγχόμενες δομές λειτουργούν αποτρεπτικά. Αναδεικνύουν την ιδεολογική άβυσσο που μας χωρίζει με τον ΣΥΡΙΖΑ” | Υπουργείο Μετανάστευσης και Ασύλου (migration.gov.gr)

- https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/#:~:text=Some%20429%2C300%20refugees%20returned%20to,with%20or%20without%20UNHCR's%20assistance).&text=Low%2D%20and%20middle%2Dincome%20countries%20host%2083%20per%20cent%20of,per%20cent%20of%20the%20total.