- 12 min read

- Published: 19th September 2018

Hard to Swallow: How Ireland could do more to tackle corporate tax avoidance

Photo caption: Oanh (27) is a dialysis patient who lives in Hanoi, Vietnam. Oanh had to leave her family home in rural Me Linh District to move to the city for the hospital treatment she needs three times a week. She can’t afford a kidney transplant and has campaigned with other dialysis patients for an increase in health cover. Photo: Adam Patterson/Oxfam

This week Oxfam Ireland released a new report entitled ‘Hard to Swallow: Facilitating tax avoidance by Big Pharma in Ireland’ which indicates that Ireland’s corporate tax rules are allowing four of the world’s largest pharmaceutical firms – Abbott, Johnson & Johnson, Merck & Co (MSD) and Pfizer – to avoid large amounts of tax by shifting profits to and through Ireland.

Based on available data, Oxfam found that Abbott paid zero tax on profits of €1.2 billion declared in Ireland in 2015, costing the Irish taxpayer an estimated €155 million that year alone. Johnson & Johnson recorded profits of €4.31 billion in Ireland in 2015 but only paid an effective tax rate of six percent, €250 million less than they should have paid at Ireland’s corporate tax rate of 12.5%. Added to the Abbott figure, that means just two of the four companies avoided €405 million in tax in just one year.

It is estimated that these four pharma giants have avoided paying annual taxes of €96.6/$112 million across the seven developing countries investigated in the report, a move which impacts on the delivery of essential services that can help end poverty and inequality.

Tax avoidance is not a victimless crime

Oxfam’s research demonstrates that corporate tax avoidance continues to drive inequality and hamper the fight against poverty. It reduces the funds available to poorer countries to invest in public services that enable communities to lift themselves out of poverty. This is particularly the case for girls and women, who make up the majority of people living in poverty – and who are more likely to rely on public services.

This is not a new phenomenon. Developing countries are estimated to lose around US$100 billion annually through corporate tax avoidance, which deprives them of vital funds for hospitals, schools and other essential services. For example, in 2017, 1,317 children died at a hospital in Gorakhpur in India. A leading cause of death there is acute encephalitis syndrome, a mosquito-borne disease that can be easily prevented with proper sanitation and hygiene, but not easily cured. According to the former Health Secretary of India, 95% of the deaths could have been prevented if India had a functioning health system.

Had the Indian government received the estimated €63.8 million the four US drug companies may have underpaid in taxes annually, it could have allocated these funds to fighting encephalitis and still have had enough money left to buy Japanese encephalitis vaccines and bed nets for every child born each year in the whole of India.

Ireland’s tax code has already been implicated in facilitating some of this revenue loss - in 2017 Google was ordered to pay taxes on €194 million of profit to the Indian government which were found to have been illegally booked in Ireland.

Last week the Financial Times reported that nine out of 10 Fortune 500 companies are being investigated for tax avoidance related to $23 billion of revenue. It is not unreasonable to suspect that Ireland’s corporate tax regime is involved in some of these cases.

More tax transparency needed

Ireland has received one of the highest international ratings on tax transparency from the OECD. However, what is termed ‘tax transparency’ by the OECD and the Irish Government refers to information exchanges between tax authorities. None of this information is published or made available to legislators, investors, journalists and civil society actors. ‘Tax transparency’ is the only form of transparency that doesn’t allow public access to information.

In 2017 the European Parliament agreed a proposal for public country-by-country reporting, which would require multinational companies (MNCs) to disclose where they generate profit and where they pay tax. However, the Irish Government has not been supportive of this proposal despite an endorsement by Brian Hayes MEP who said:

“The measures agreed by the Parliament represent a major step forward for tax transparency. Europe is leading on this issue alone. Country-by-country reporting is coming whether multinationals like it or not and I believe tax information for large companies should be made public as long as it is fair and is in the public interest… Fine Gael is in favour of corporate tax transparency.”

The current lack of transparency impedes attempts to understand how countries’ tax regimes operate. Because the companies in the Hard to Swallow report reveal little about their subsidiaries’ finances, attempts to quantify their tax avoidance barely scratch the surface. We limited our inquiry to countries where we could find a critical mass of data, and for those countries we located data for just 358 out of 687 subsidiaries – 56 in seven developing countries, 218 in eight advanced economies, and 84 in low tax jurisdictions like Ireland. Oxfam cannot prove that the companies are engaged in profit shifting or tax avoidance – this would require access to the companies’ tax returns. However, increasing transparency, such as through public country-by-country reporting would provide relevant actors, especially in developing countries, with data to help review and, if necessary, reform aspects of the tax system being used purely for tax avoidance.

Ireland’s Corporate Tax Roadmap

Earlier this month the Department of Finance released ‘Ireland’s Corporate Tax Roadmap’ which outlines the existing and future measures the Irish Government plans to take to address corporate tax avoidance. While it will tackle some mechanisms used, it does not go far enough to address all of the tax dodging mechanisms employed by multinationals, including big pharma companies. Most worryingly, the plan contains few, if any, mechanisms to address corporate tax avoidance that impacts developing countries.

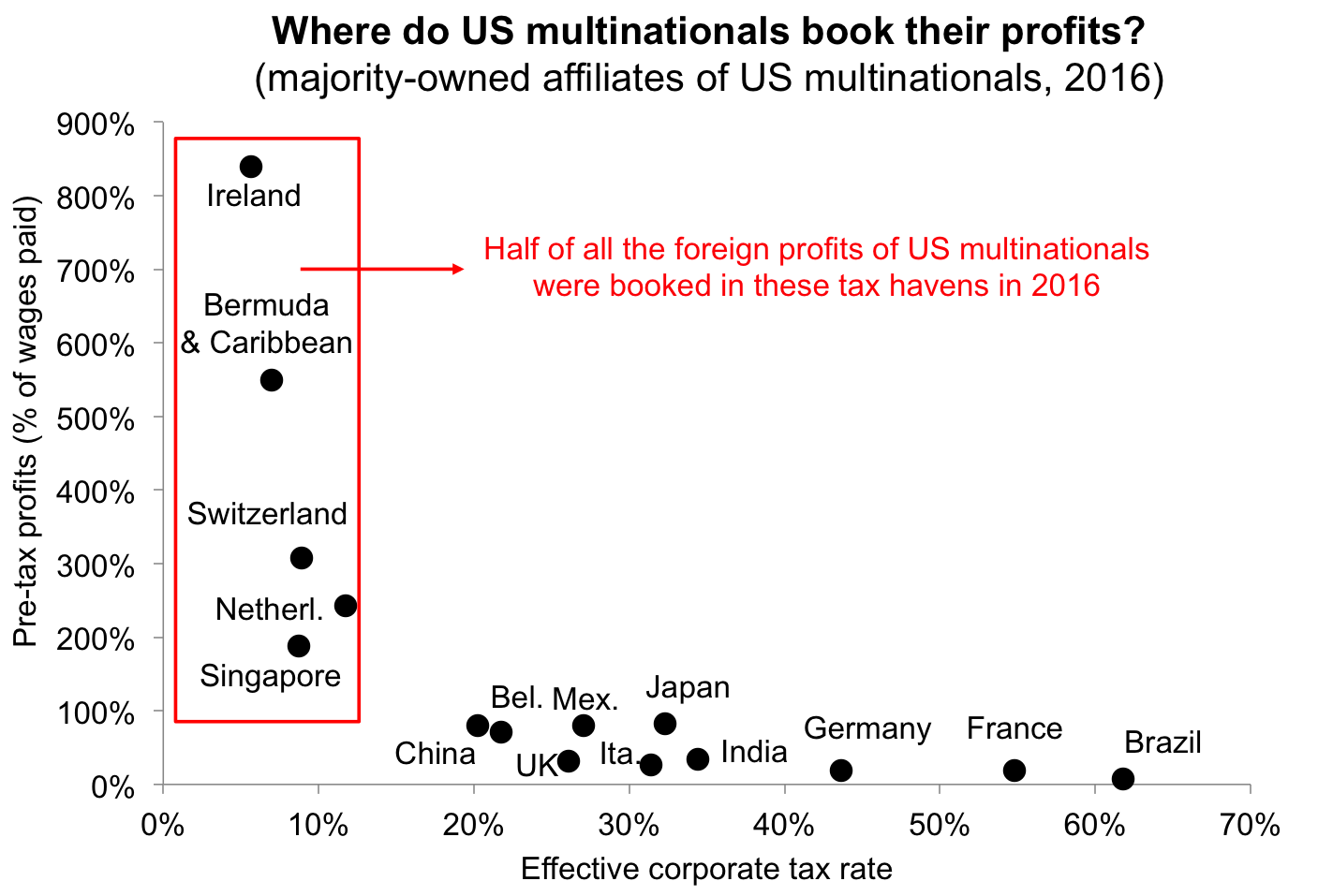

Oxfam’s Hard to Swallow report adds to the growing body of research that indicates that Ireland is still one of the world’s biggest conduits for tax avoidance. Berkeley academic Gabriel Zucman’s most recent research indicates that Ireland facilitates the largest level of profit-shifting by US MNCs.

The Hard to Swallow report also corresponds with the EU’s recent assessment of Ireland’s economy as part of the EU’s Semester Review, which stated that “some indicators suggest that Ireland's corporate tax rules are used in aggressive tax planning structures”. This review found that royalties sent from Ireland were equivalent to 26 percent of Ireland’s GDP in 2015 – more royalties than were sent out of the rest of the EU combined, making Ireland the world’s top royalties’ provider. High levels of these payments’ economic activity indicate that the jurisdiction is facilitating tax avoidance.

Despite this evidence, the Irish Government continues to claim that Ireland’s corporate tax regime doesn’t harm developing countries. It bases this claim on the findings from a spillover analysis undertaken in 2015 which concluded that “the Irish tax system on its own can hardly lead to significant loss of tax revenue in developing countries”. One of the arguments for this is that the amount of financial flows from Ireland to developing countries is low.

However, this spillover analysis only looked at limited data, focusing on 13 countries over two years. This meant that only 4 percent of the available data on Irish overseas investment into developing countries – from 2009 to 2012 – was examined. It also didn’t look at indirect flows through third countries like Luxembourg or Bermuda. Moreover, not all the limited data analysed could be assessed due to secrecy laws. The analysis noted this flaw saying that “a substantial percentage of [foreign direct investment] is labelled “confidential (…)” or “unspecified (…)” and this may in part go to developing countries”. Finally, the analysis ignored assessments of capital gains related to the sale of cross-border investments. Instead it focussed on the taxation of income from cross-border investments and services in contrast to the IMF’s Fiscal Spillover Reports.

At the end of 2017, Christian Aid Ireland published two reports entitled Global Linkages and Impossible Structures critiquing the Irish spillover analysis and highlighting the many mechanisms still available under Irish tax law that facilitate corporate tax avoidance.

Changes to be implemented before the end of 2018

So, what new mechanisms are outlined in Ireland’s Corporate Tax Roadmap to address corporate tax avoidance? Firstly, all of the items outlined in the roadmap are either compulsory under EU law (as per the Anti -Tax Avoidance Directive or ATAD) or have already been signed up to by Ireland. The details in the plan concern how and when Ireland will be implementing these existing commitments. Unfortunately, Ireland has chosen to implement the least effective of these tax avoidance mechanisms at the latest available date. Most worryingly, these proposals include little or no mechanisms to address corporate tax avoidance that negatively impacts developing countries.

Most of the plan will not be implemented immediately, with some items not due to come into force for five years; however, three items are planned to be introduced before the end of 2018.

The first is the ratification of the OECD’s Multi-Lateral Instrument (MLI) by the Dáil by the end of this month. The MLI is an attempt to provide common minimum standards for all existing and future Double Tax Agreements (DTA). A DTA is legal agreement between countries to determine the cross-border tax regulation and means of cooperation between the two jurisdictions. DTAs often revolve around which jurisdiction has the right to tax cross-border activities and at what rate.

The minimum standards set out in the MLI have been designed to close tax avoidance loopholes. Article 12 of the MLI relates to defining when an MNC has a taxable presence or permanent establishment (PE) in a jurisdiction. This article makes it harder for multinational companies to claim that they don’t have a permanent establishment/taxable presence in a third country if they use a third party to conclude contracts on the company’s behalf, an approach that can be used as a tax avoidance strategy. When Ireland signed the MLI in June 2017 it chose not to adopt Article 12, missing the opportunity to close this loophole.

In its submission to the consultation process that informed Ireland’s Corporate Tax Roadmap, Oxfam recommended that Ireland should adopt article 12 of the MLI when it ratifies the MLI later this year. No reference or discussion of this is included in Ireland’s Corporate Tax Roadmap, despite the Minister of Finance’s commitment to review this issue following news reports about the continuance of this loophole.

The second item Ireland proposes to introduce are controlled foreign corporations (CFC) rules, which, if designed appropriately, can make it less attractive for a company to shift profits to avoid tax. CFC rules can also discourage shifting profits from subsidiaries in developing countries to tax havens for EU-headquartered companies. Ireland has chosen to implement a form of CFC rules that will do little to address corporate tax avoidance. They will assess whether artificial arrangements (arrangements set up for mere tax purposes and not in line with the economic reality) are being used to avoid paying tax – something that Ireland is already supposed to be doing under its current transfer pricing legislation. The problem with this is that although it looks at artificial arrangements, it is very hard for Revenue Authorities to prove whether a structure is artificial or not.

The final change that should be implemented before the end of 2018 relates to updating Ireland’s domestic transfer pricing legislation, especially related to non-trading income, including capital transactions. Although these changes are welcome, Oxfam does not feel that addressing profit-shifting out of Ireland alone is enough to truly tackle corporate tax avoidance. Oxfam has asked that ‘two-way’ transfer pricing legislation is needed to give Irish Revenue officials the power to investigate instances where profits are shifted from a high tax jurisdiction to Ireland, to avail of its low corporate income tax rate. This would allow officials to identify potential abuses which could lead to revenue losses in other countries, especially developing countries.

The ‘Coffey Review’ stated that there are adequate measures in place to address this issue. The review asserted that if transfer mispricing occurs, a foreign tax authority may adjust the transfer prices charged or taken by a foreign affiliate resident in their territory and attribute a higher quantum of taxable profit to the affiliate. If the Irish Revenue agrees with this assessment, an adjustment can be made under protocols set out in relevant Double Taxation Agreements. However, not all tax authorities of developing countries have the capacity to undertake such audits and identify sophisticated tax avoidance strategies. The Coffey Review also asserted that there is a danger of double non-taxation if the other jurisdiction decides not to exercise its taxing rights. This concern can be easily addressed by inserting a protection clause in new legislation to ensure that a reduction in taxable income in Ireland will only happen when Revenue is satisfied that the income will be assessable in another jurisdiction.

There should be more consideration in Ireland’s Corporate Tax Roadmap of the more comprehensive mechanisms needed to address corporate tax avoidance in a digitalised and global economy. These mechanisms include taxing companies on their global profits and then apportioning tax revenue according to value creation and economic activity, the development of a global minimum effective tax rate and the implementation of public country-by-country reporting. Although the Irish Government recognises that additional reforms are required to take account of the highly digitalised global economy “to ensure that tax is paid by companies where value is actually created”, it does not support any role for developing countries in this process.

What Ireland needs to do

Besides draining money from essential services, tax dodging also negatively impacts the poor because it requires governments to raise a greater proportion of their revenue from other sources. Most developing countries raise two thirds or more of their tax revenue through consumption taxes, which eat up a larger proportion of income, the poorer you are.

Ireland has a well-earned reputation of acting fairly and being a champion of the rights of poorer countries. To ensure this reputation is maintained, it needs to do more to address corporate tax avoidance that impacts the world’s poorest people.

Ireland is calling on the Irish government to:

- Support efforts at EU level to agree meaningful legislation on public Country by Country Reporting

- Advocate at relevant global forums for a consensus to be reached on a global minimum effective tax rate

- Address profit-shifting, including signing up to Article 12 of the OECD’S Multilateral Instrument.

- Review and reform Ireland’s Double Taxation Treaties

- Strengthen Ireland’s existing Exit Tax regime and subject all new tax incentives to rigorous economic and risk assessments

- Contribute to a second generation of international tax reforms to address the use of highly mobile value, including IP and other intangible assets.

- Ensure that developing countries participate in all discussion concerning corporate tax reform on an equal basis